Global bonds rallied in February and March, giving the unfortunate illusion that bonds are an important part of a portfolio managed to a fiduciary standard. But there is no justifiable reason left to take on the duration risk (and potentially the credit risk) of domestic and foreign Treasury bonds. Only complacency and fear of change keep Treasury investors entrenched.

Investors have historically owned sovereign and investment-grade debt for a few reasons:

- It provides a core base return for their overall portfolio.

- It is expected to provide positive returns during equity sell-offs.

- They’ve always allocated to bonds.

- Allocating 100% equities is too risky. (Cash and equities are the only two relevant liquid allocations, unless you haveaccess to high-quality, liquid alternatives)

While these reasons have been true in the past, much has changed. Bonds no longer provide an attractive base return, with current 10-year yields less than 1% and a majority of sovereign debt yielding zero or less. The positive returns during spring’s equity sell-offs were merely a mirage generated by federal intervention rather than from natural market forces.

Having any sovereign or investment-grade debt is a bad investment decision for the following reasons:

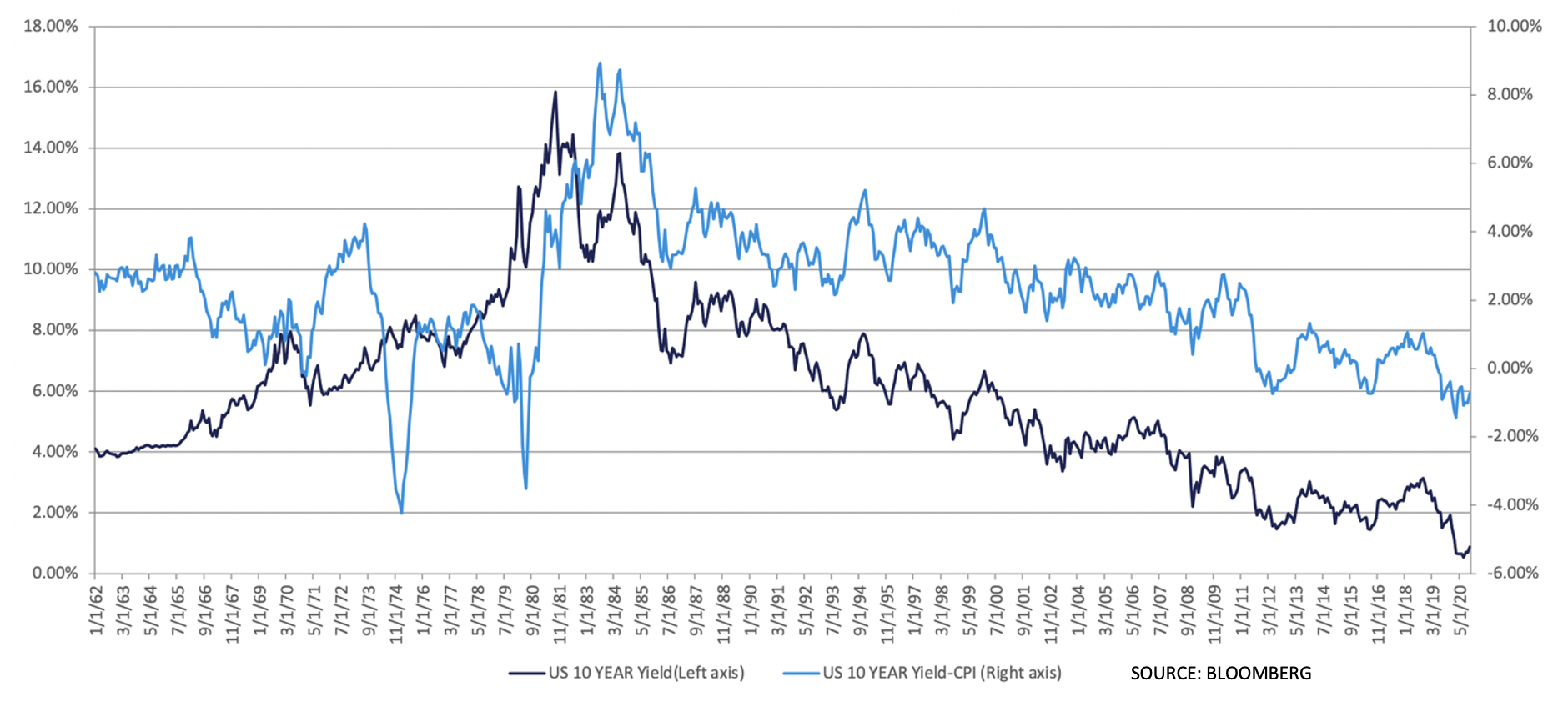

- Historically, the 10-year note yielded at or above realized inflation. Given inflation rate expectations in the next 12 months of close to 2%, this implies a loss of 10.1% given a duration of 9.44 years on 10-year Treasury bonds.

- Current inflation rates are 1.5% +/- with all the kindling to drive it higher, not lower.

- The buyer base of Treasury securities is drying up with the Fed being the buyer of last resort.

- The Fed artificially creates low rates and demand in times of crisis to add liquidity to the system.

- Investors are fatigued trying to short the Treasury market for the last seven years. Complacency is high.

- Investors forget the muted response of Treasury securities to the sell-offs in February 2018 and the third quarter of 2015 when the Federal Reserve was not there to prop up bonds.

- The market dynamics supporting equities, zero interest rate policy (ZIRP), and extreme liquidity is unsustainable policy that makes both asset classes prone to the same risk.

As rates have fallen, duration has gone up along with negative convexity, leading to definitionally more negative asymmetric risk holding Treasury bonds.

I am not arguing that bonds don’t have portfolio advantage or that they will trade lockstep lower with an equity sell-off; I can still see the benefit of tactical programs that take advantage of the shape of yield curves. I am arguing that the likely risk offset from bonds will be minor while the primary disadvantage is the risk of bond prices achieving yields to merely match a 2% inflation rate. Until the coupon rate matches expected inflation, investors are very likely to have a negative yield from this allocation with very little protection from an equity sell-off.

For investors with access to private debt markets, there may be a better source of return, but it will not provide a boost in an equity sell-off. However, if an investor were to take the excess return from private debt yield above inflation and apply the net interest to equity puts, one would have a better portfolio solution with higher returns and stronger equity downside protection. Almost any form of equity protection is better than bonds, as is any form of extra excess yield from private credit.

Still think bonds are a worthy addition to your portfolio? Let’s take a look at some evidence that proves this asset class is not worth the attention:

A Selection of Bond Reactions to Equity Sell-offs

- 2008: Rallied 25% (10-year bonds), but quickly gave back half the yield.

- 2011 (Q3+Q4): Rallied 14% and kept the gain.

- 2015 (Q3): No real response.

- 2018 (February): No real response.

- 2018 (Q4): Rallied to recover losses from 2016 (fear of aborted economic recovery).

- 2020 (March): Rallied 10% (driven by the Federal Reserve).

There is a clear trend here: rallies are less powerful with equity sell-offs and require more government intervention to create the intended effect. It quit working after 2011.

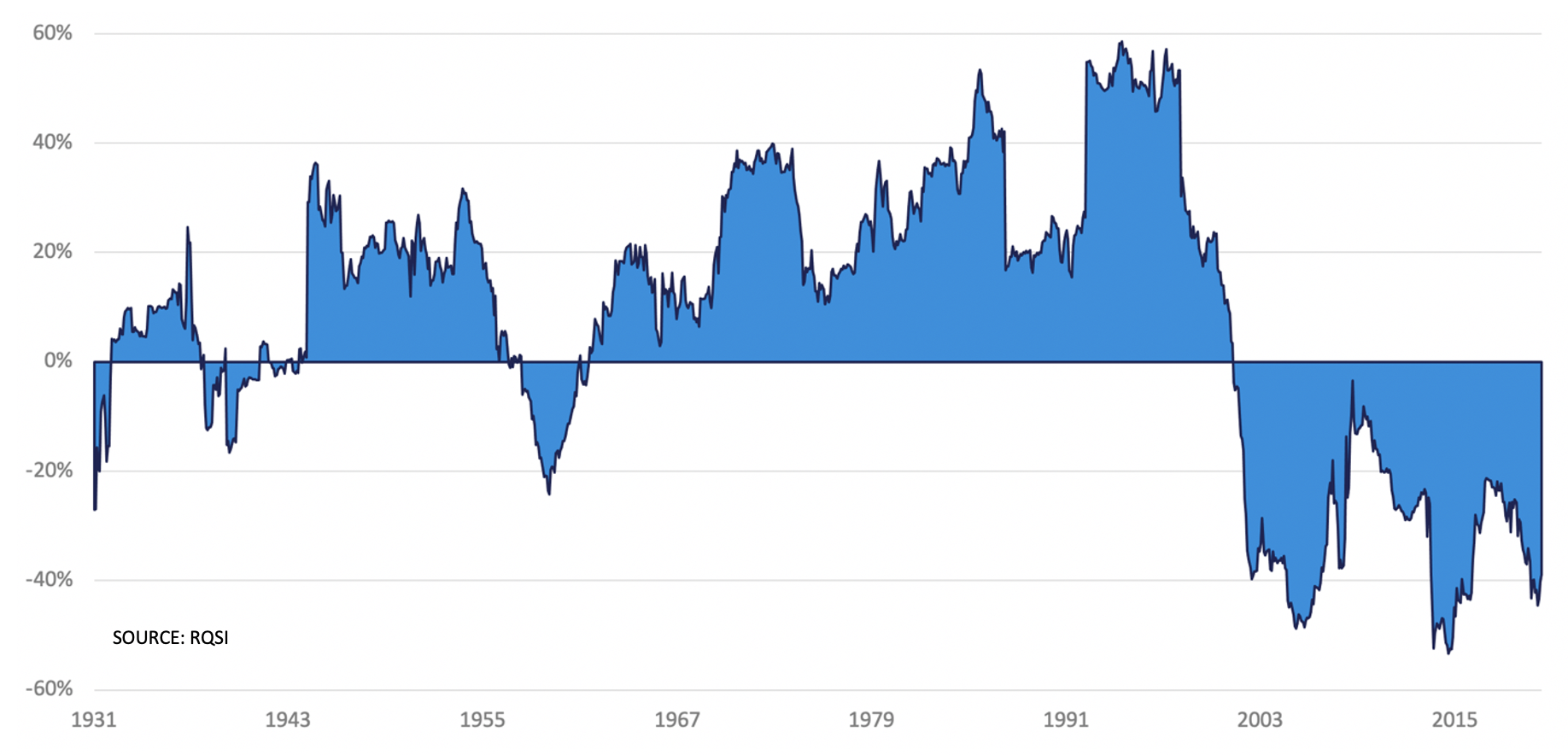

Rolling 5-Year Correlation of US Equities to US Bonds

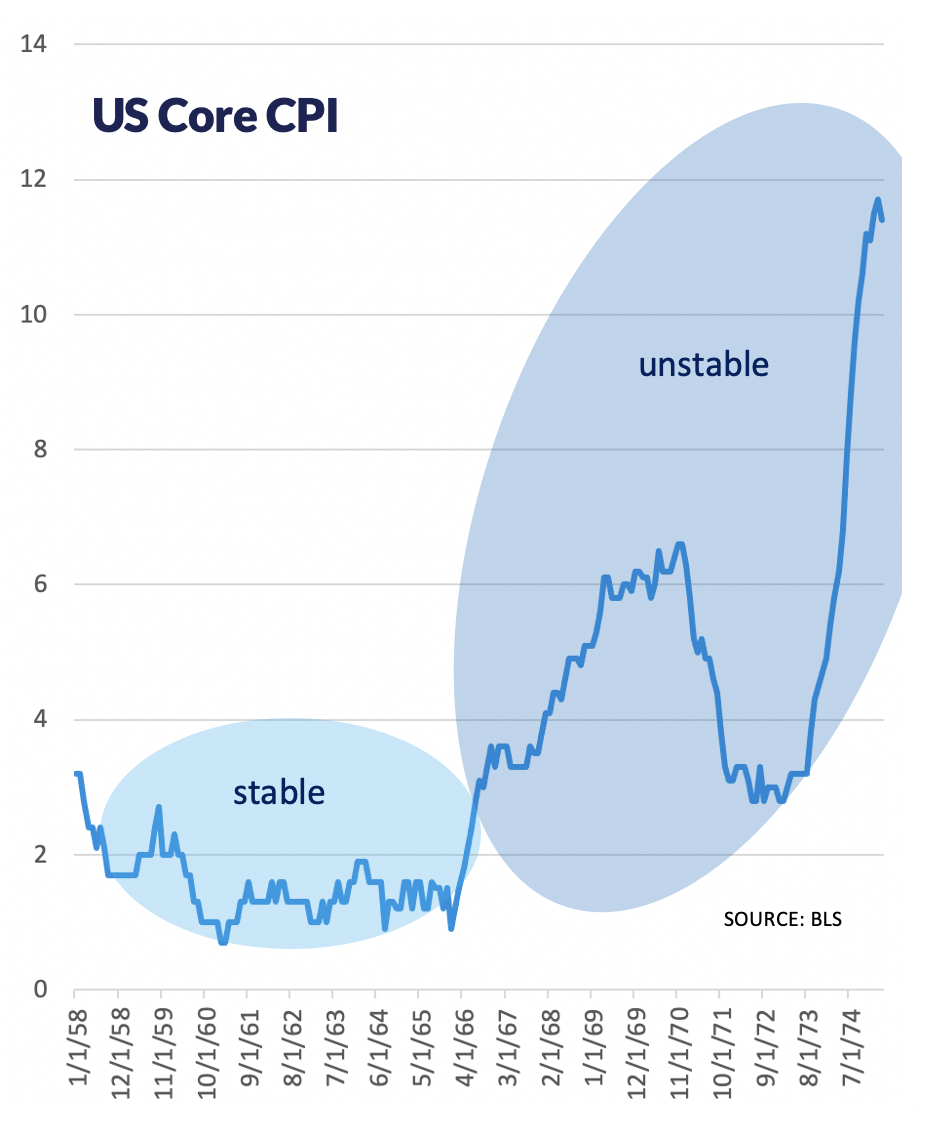

The last 20 years of negative correlation are less the norm than the previous 80 years. The correlation effect may not hold going forward. Nominal yields have been falling for the last 20 years and are at historic lows while Real Yields are negative. I seriously doubt either is sustainable.

10-Year Treasury Note Yield

Nominal yields have been falling for the last 20 years and are at historic lows while Real Yields are negative. I seriously doubt either is sustainable.

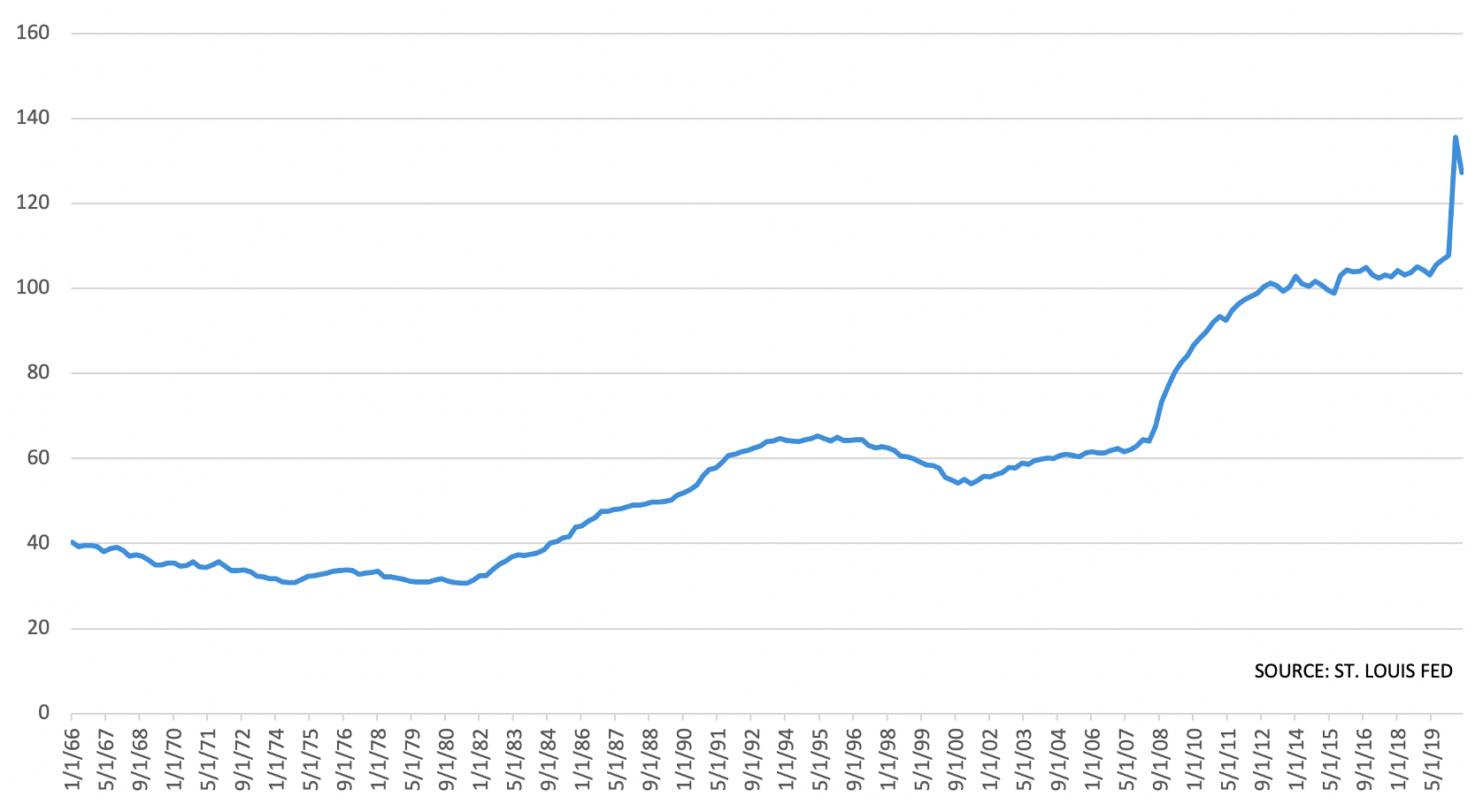

Total Public Debt as Percent of Gross Domestic Product

The federal debt has skyrocketed. What will this look like during the next economic recession?

Conclusion

There is so much momentum and fear when considering a fundamental shift in an allocation scheme that has been considered a given by all investment professionals. Yet, what good is a negative note like this without a recommendation for an alternative action? I recommend a few potentials:

- Sit in cash and don’t get anxious.

- Professional private lending offers higher real yields. Investors can use the excess return over inflation to buy puts on the S&P 500.

- U.S. investors should consider buying gold as an inflation and dollar hedge.

- Consider market-neutral approaches in liquid alternatives.

- I would not suggest increasing your equity exposure, as a cautionary piece on U.S. equity exposure can be made just as easily. This is not an ideal time to add risk to your portfolio.

Back to your fixed income allocations, you now have three choices:

- Remain in your fixed income portfolio and weather the very likely coming storm.

- Wait until reducing this exposure becomes “acceptable.”

- Be proactive and acknowledge the reality of the market, ridding your portfolio of a useless allocation.

Which path will you take?